Slow Burn Likely Until Coronavirus Vaccines Are Widely Available

Resurgences in outbreaks make it clear that ending the pandemic will require more than diagnostic testing, contact tracing, and social distancing.

Since our May update, U.S. coronavirus cases have surged higher than we expected for several reasons.

- Initial increases in cases have not been consistently met with a pullback in reopening plans or more aggressive individual efforts at good hygiene, masking, and distancing.

- The supply of diagnostics has increased, but shortages still exist, and long turnaround times can make results irrelevant unless patients opt to self-quarantine while waiting for results.

- Contact tracing has been hampered by the sheer number of cases to trace with limited staff, long diagnostics wait times, and poor uptake for app-based tracing technologies.

In a JAMA interview in June, Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, said transmission for COVID-19 won’t follow the wave pattern we have seen with influenza pandemics. He expects ongoing transmission in the United States could look more like a slow burn, likening the pandemic to a forest fire and uninfected individuals to remaining wood to burn, with hills and valleys in the outbreak in different regions.

Despite continued efforts to improve diagnostics capacity and turnaround times, including new technologies that could open up a wider supply of diagnostic tests that can generate rapid results, we think the U.S. is likely to struggle with a continued slow burn until we have an adequate supply of vaccine to tip us toward herd immunity.

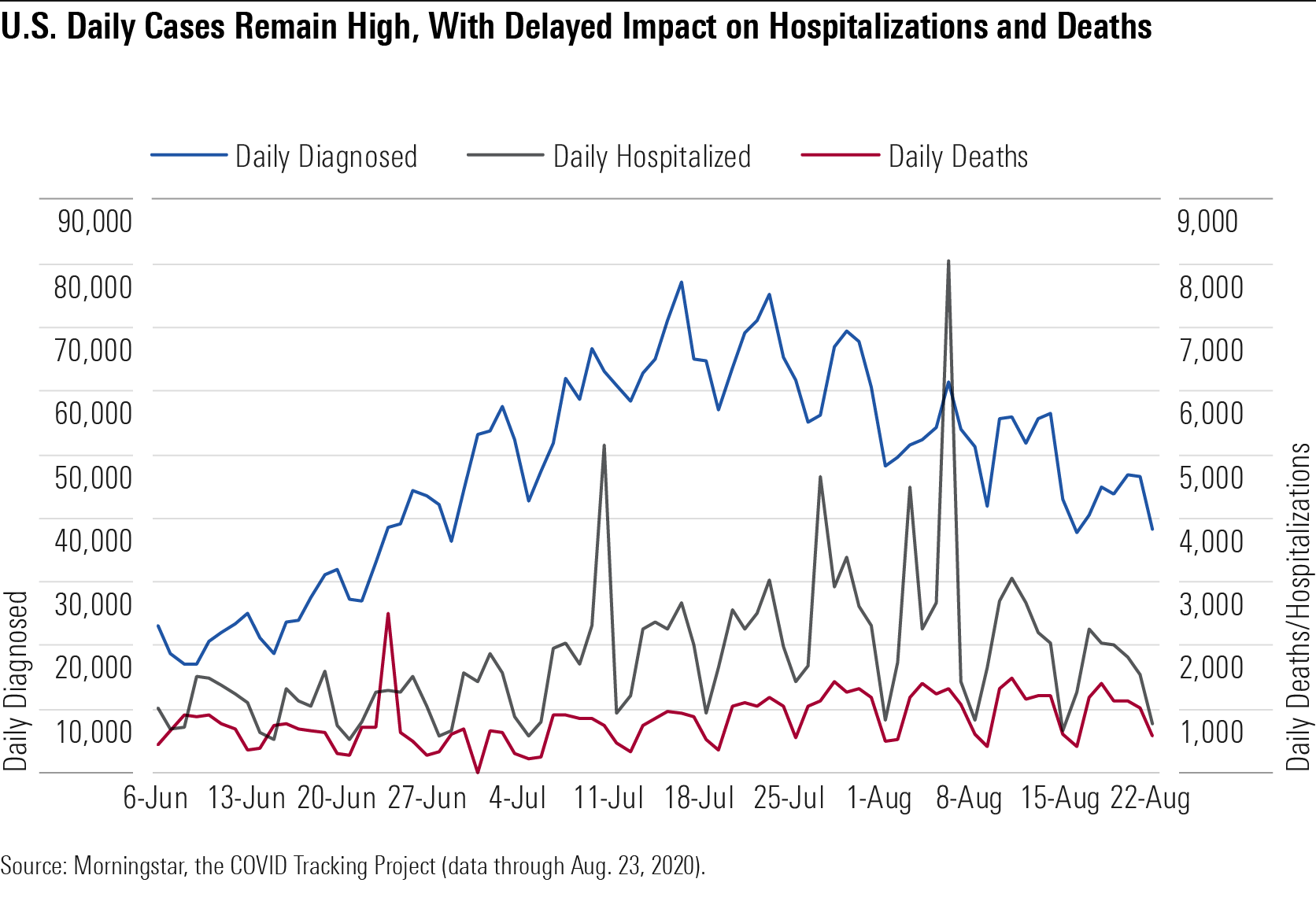

Updated Forecast: Death Rates, Infection Rates, and Positive Diagnostic Tests Our updated U.S. coronavirus forecast assumes 274,000 deaths and nearly 20% infected by the end of 2020. Daily U.S. diagnoses bottomed out in May around 20,000 but steadily climbed in June and July and remained high in August at around 50,000 per day. Hospitalizations and deaths tend to lag diagnoses; on average, it takes five days for a person to develop symptoms, but it can take weeks for a patient to die from COVID-19. Cases seem to be skewing younger, leading to a lower death rate, but daily U.S. deaths are now typically back above 1,000 a day after dipping below this for June and the first half of July.

U.S Daily Cases Remain High, With Delayed Impact on Hospitalizations and Deaths

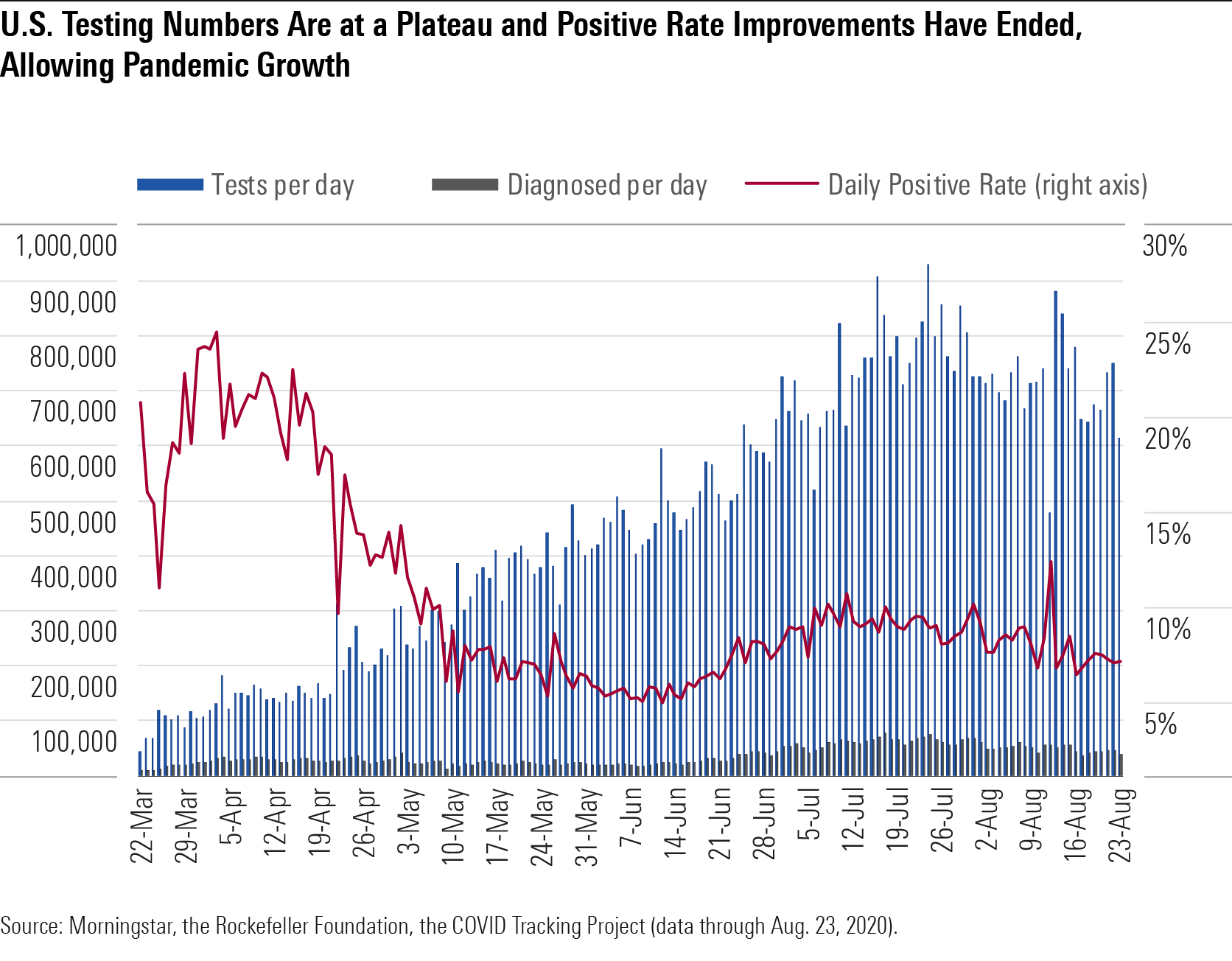

The percentage of diagnostic tests that come back positive is one key indicator of the level of control over an outbreak. This positive rate bottomed out around 4% overall for the U.S. in early June and is now back up to the mid- to high single digits. Broader availability of diagnostic testing today allows for a much lower positive rate than during the initial surge in March and April and is also leading to a higher portion of the diagnosed population with mild or moderate disease, as capacity constraints in March and April meant that those with severe disease were the most likely to be diagnosed.

The death rate is also falling, probably because cases today are averaging at a lower age (likely influenced by the reopening of restaurants and bars and better safeguards around long-term care facilities). It’s also possible that hospitals are getting better at treating severely ill patients, with better access to drugs like remdesivir and dexamethasone and better standards of care.

But while a surge may start in a healthier, younger population, it’s hard to keep infections isolated from older populations in the long run if infection levels in society remain higher. We are likely better at protecting the elderly than we were during the initial spread beginning in March, but with 64 million Americans living in multigenerational households, it is difficult to protect the elderly when students and younger adults return to school and work. In addition, epidemiologists estimate that the U.S. is still only diagnosing roughly 10% of cases, meaning that most infected individuals are in a position to unknowingly infect their close contacts.

Using published numbers on diagnoses so far, and assuming slow improvement in the roughly 10% diagnosis rate that epidemiologists continue to support, we think roughly 9% of the U.S. population has been infected through the end of July, consistent with a model produced by several epidemiologists and public health experts from the Yale School of Public Health and Yale School of Medicine. Their analysis, based on published state data and assumptions for mortality and other disease characteristics, also averaged at a 9% prevalence rate.

We assume that nearly 20% of Americans are likely to be infected, overall, by the end of the year. This assumes a small drop in daily infections steadily throughout the remainder of the year, as aggressive reopening plans initiated in May and June are being somewhat rolled back and more mask mandates are now in place. In addition, prophylaxis therapy with targeted antibodies or vaccines should start to become available in the fourth quarter, which we expect to counter increased risk from more indoor gatherings as a result of the start of school and cooler weather.

Diagnostic Testing Hits Its Limit for Established Technology Capacity The daily volume of COVID-19 diagnostic tests has grown significantly over the past two months, but the lack of centralized testing management in the U.S. has led to local supply shortages and difficulty matching supplies with available platforms. Demand has also intensified, outstripping the supply of kits.

In addition, we are approaching what we see as the maximum testing supported by RT-PCR testing platforms, which amplify genetic material of the virus from samples but require lab processing and a time-consuming process of cycles at different temperatures. One-week wait times for results from these tests in some areas make it difficult to reduce further transmission, and as the pandemic spreads, consensus is that speed matters more than sensitivity in COVID-19 testing.

We expect incremental improvements in supply with better coordination of labs and pooled PCR testing (testing multiple samples together) but also potentially larger increases in supply this fall with the embrace of less sensitive but cheaper and much faster tests, including antigen tests and new CRISPR-based tests. Labcorp LH has improved to 180,000 daily tests and two- to three-day turnaround times as of late July, and Quest DGX plans to expand to 185,000 by the start of September, allowing two- to three-day turnarounds as well.

The Food and Drug Administration authorized Quest to pool samples from up to four patients and authorized LabCorp’s test to be used in asymptomatic individuals or pooled tests for up to five samples in July. Hologic HOLX filed for an emergency use authorization, or EUA, for its tests in August. These authorizations could be particularly helpful as we screen larger populations. Ultimately, pooled testing is most useful at lower positive rates; otherwise, many tests would need to be rerun individually at higher expense.

U.S Testing Numbers Are at a Plateau and Positive Rate Improvements Have Ended

Antigen tests and new technologies could help us achieve faster, point-of-care results and improve access to testing, but it could be several months before this becomes widespread, and current antigen tests involve some sacrifice in test accuracy. In late July, the National Institutes of Health announced a $250 million investment in seven diagnostics firms as the culmination of the Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics, or RADx, initiative, which could boost diagnostics access by millions per week beginning in September.

The RADx goal will require increased use of antigen-based tests and novel test approvals. Antigen tests detect proteins made by the virus; the first, by Quidel QDEL, was approved in May and rolled out in urgent care centers. A second approved antigen test from Becton Dickinson BDX can produce results in 15 minutes. The proteins can’t be amplified easily to gain a more sensitive test; therefore, there is typically a high false negative rate. That said, these tests tend to detect the sickest patients, who are likely to be the ones most capable of transmitting the virus.

We’re encouraged by the Aug. 26 news of Abbott’s ABT EUA for a 15-minute lateral flow antigen test, which will be priced at $5. Because this requires no equipment (although it does require a healthcare professional to administer the nasal swab), it will bypass the bottlenecks at labs. A complementary app will allow those who test negative to show a health pass for entry into facilities. Scale is critical to the test’s relevance, and we think this could have a significant impact on testing by October. Also, the test can detect 97% of positive cases. Perhaps similarly, E25Bio is working on a lateral flow rapid diagnostic test (similar to a pregnancy test) for COVID-19 that is based on antigen detection but eliminates the need for instruments.

Newer technologies that can amplify genes using CRISPR gene editing technology or use chemicals to detect small amounts of virus could also allow for fast and perhaps more sensitive point-of-care testing than Abbott’s RT-PCR point-of-care test and Quidel’s and BD’s antigen tests. The first CRISPR-based diagnostic, from Sherlock Biosciences, has been approved by the FDA, and Glaxo GSK and Mammoth Biosciences are working on another, even faster (20-minute) CRISPR-based test. Also, a saliva-based testing method from Yale was granted an EUA in mid-August; given that the technology is open for other labs to use and does not require special collection tubes, this could be another avenue to opening up testing capacity.

Cases, Diagnostic Testing, and Contact Tracing Capabilities Vary Widely by State While we've previously cited the 10% positive rate benchmark as the one given by the World Health Organization to control a pandemic, the WHO advised on May 12 that a 5% positive rate was necessary for countries to reopen safely, and the Harvard Global Health Institute's recommendations translate to a 10% positive rate for stabilization and a 3% positive rate for suppression. Positive rates lower than 1.5% have been achieved in several European countries. Data from the U.S. over the week of Aug. 8-15 shows that few states are achieving the 3% positive rate needed for suppression, with most teetering near the boundary between stability and growth.

Conventional contact tracing (social workers who interview patients and call contacts to improve awareness of potential exposure and reduce spread of the virus) has proved slow and difficult to roll out. This is partly due to issues with diagnostic testing (inadequate supply of tests and long turnaround times for results) but also due to the fact that contact tracing is difficult to impossible to perform when case counts are high.

Even though contact tracing could theoretically push transmission down 45%, we are far from being able to detect 90% of symptomatic cases and their contacts, which would be required to achieve this. These problems are exacerbated by growing skepticism of the government response to the pandemic and undersized local public health systems. App-based tracing has been minimal due to low uptake.

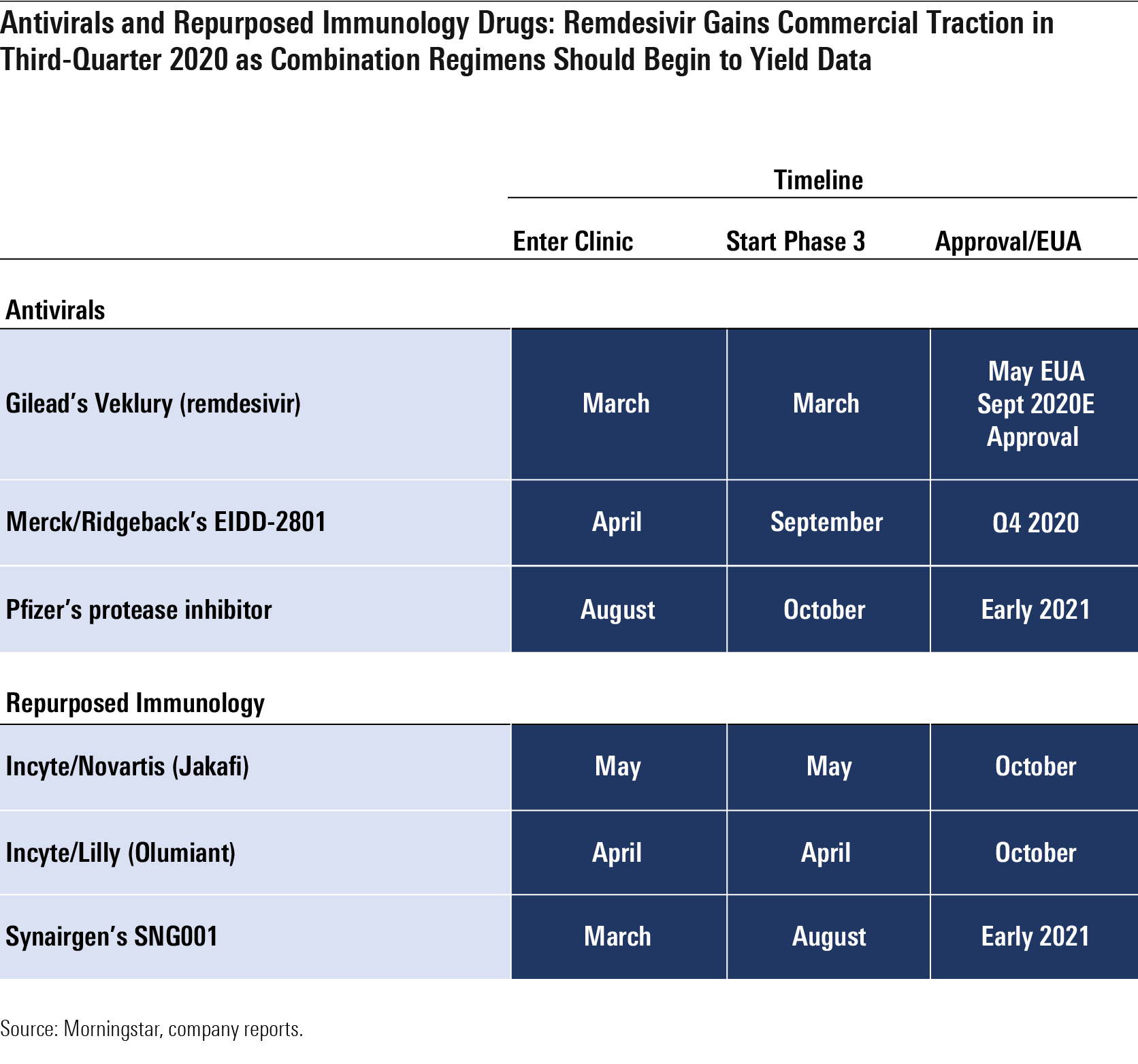

Antivirals and Repurposed Immunology Drugs: Remdesivir Gains Commercial Traction in Third-Quarter 2020 as Combination Regimens Should Begin to Yield Data

Antivirals and Other Coronavirus Treatments Progress with coronavirus treatments has been mixed. By the end of the year, we expect data on new antivirals and whether combinations of Gilead's GILD remdesivir combinations with oral antivirals like Pfizer's PFE protease inhibitor or Merck/Ridgeback's MRK EIDD-2801 improve on remdesivir alone.

- Remdesivir. We think remdesivir, which received an EUA in the U.S. on May 1 (and for which an official FDA new drug application was later filed), has a place in the near term to midterm as a treatment for patients who are hospitalized with COVID-19 but not yet on mechanical ventilation, although we expect vaccines and other coronavirus treatments to reduce demand significantly beyond 2021, and we only model sales through 2023. We assume peak sales of nearly $3 billion in 2020, using a $2,340 price and 1.2 million treated commercial patients as our key assumptions. Gilead also started a phase 1 trial of inhaled remdesivir in healthy volunteers in July, with the aim of testing this method of administration in COVID-19 patients in August. An inhaled version could allow Gilead to treat nonhospitalized patients, potentially preventing hospitalization in some patients (the current infused version would be difficult to extend into healthier patients). Overall, we estimate that roughly 1.2 million patients could receive the commercial drug in the second half of 2020 at the five-day dosing schedule.

- EIDD-2801 is an oral nucleoside analog that has shown preclinical efficacy as a coronavirus treatment and preventive antiviral in SARS and MERS; the drug improved pulmonary function, decreased weight loss, and reduced the amount of virus in the lungs. In its phase 1 trial, which started in the United Kingdom in April, the drug had solid tolerability data, leading Ridgeback to start two phase 2 studies in June (the 2004 study in hospitalized patients and the 2003 study in patients at home), both testing whether patients become free of virus. Ridgeback expects to have 1 million courses available by fall, and a phase 3 trial is planned to start in September, which we think could allow the drug to compete with remdesivir in 2021 and expand its reach into patients who are sick at home, where intravenous remdesivir is not practical.

- SNG001, the inhaled interferon from Synairgen SYGGF, offered promising data in July (via press release) that pointed to reduced potential for developing severe disease and greater likelihood of recovery for patients taking the drug versus those on placebo. The SNG001 study had only roughly 100 hospitalized patients, Synairgen did not publish information on the primary endpoint (28-day improvement), and it is unclear if the results are statistically significant; however, injectable beta-interferon is now entering an NIH-sponsored study in combination with remdesivir.

- JAK inhibitors Olumiant and Jakafi are expected to provide data in the coming months, although repurposed immunology drugs so far have a poor record, with IL-6 antibodies Actemra and Kevzara failing to improve outcomes.

Passive Immunization as a Coronavirus Treatment: Higher Price, Smaller Niche Passive immunization involves administering antibodies to prevent disease; unlike vaccination, it does not require the patient to mount an immune response in order for the antibodies to be effective. These antibodies can be from a recovered patient (convalescent sera) or from a lab (engineered monoclonal antibodies designed for similarity to the most potent neutralizing antibodies from natural infection). We expect monoclonal antibody therapies have more promise than convalescent sera, as they provide a more uniform product, are likely more effective, and can be made at a much larger scale.

We expect demand for these antibodies to be highest before an effective COVID-19 vaccine is available (to prevent and treat COVID-19) but also significant on a smaller scale afterward (to treat unvaccinated individuals or as prophylaxis in those for whom a vaccine is ineffective). Monoclonal antibodies do require large bioreactors used to make other therapeutic antibodies, like for approved oncology and immunology treatments. There is likely enough supply for treatment but not for chronic prevention dosing on a large scale in the absence of a vaccine, and prices will be much higher than a vaccine.

Despite these challenges, we expect targeted antibodies to be met with strong demand, if effective, at least through the first half of 2021, while vaccines are still ramping production. Antibodies could be particularly useful as coronavirus treatments and preventive measures for older adults at high risk of exposure, as older adult immune systems may not respond as well to vaccination.

While initial data from mRNA vaccines shows solid antibody responses for elderly volunteers, even high levels of antibodies are not necessarily protective from infection for the flu in the elderly, so it will be important to monitor clinical studies in the elderly for continuing T-cell responses and ultimately for the ability to lower rates of infection in phase 3 trials.

We Assume 2021 Sales of $6 Billion for Regeneron's REGN-COV2, a Promising Coronavirus Treatment Operation Warp Speed has signed a contract with Regeneron REGN for its engineered monoclonal antibodies (based partly on the most effective antibodies produced during natural infection). A cocktail of two such antibodies, which entered testing in June, could be less likely than other antibody programs to lead to resistant viral mutations. While antibodies are among the most promising therapies for COVID-19, hurdles remain due to cost, manufacturing capacity, and the expected duration of protection. However, Regeneron's recent deal with Roche RHHBY expands manufacturing capacity, and several other antibody programs--from companies including AstraZeneca AZN and Lilly LLY--have entered clinical trials.

Overall, we see Regeneron’s antibody cocktail as highly likely to receive an FDA EUA this year, and we assume a 60% probability of approval despite a current lack of clinical data. In theory, monoclonal antibodies should be a more refined version of convalescent plasma, as they offer a more targeted antibody solution and can better control potency.

Regeneron started two clinical studies for antibody cocktail REGN-COV2 in June, and late-stage development as a coronavirus treatment began in July; the company expects initial data in September. It is also conducting a prevention study with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases that began in July. We assume emergency use could begin in the fall. However, we have seen delays with clinical trial enrollment due to diagnostic testing access (patients must be enrolled within seven days of developing symptoms, which can be a hurdle, given diagnostic turnaround times) and overwhelmed hospitals (initiating new clinical trials and bringing infected but unhospitalized patients into a hospital can be challenging).

Regeneron is quickly ramping manufacturing capacity for the cocktail and will potentially supply millions of doses per month from its New York facility by 2021. Given the significant increase in manufacturing capacity, we now assume $6 billion in probability-adjusted peak sales in 2021 ($10 billion in sales, if approved), with roughly half the economics going to Regeneron and the other half to Roche (50%-60% of worldwide gross profits are expected to go to Regeneron). This implies roughly 3 million patients globally receiving treatment at a price around $3,000 (similar to the price of Gilead’s remdesivir), or a similar number receiving several months of prophylaxis dosing, which represents a very small subset of the over-65 population even in the U.S. (46 million) and the over-75 population (more than 20 million in the U.S.).

Several other antibody programs are entering diagnostic testing, but Regeneron’s program is the most advanced and is distinguished from most with its cocktail strategy. We assume sales decline beyond 2021 and disappear by 2023, as vaccination rates in society should lead to herd immunity, reducing the need for ongoing coronavirus treatment or preventive therapy with antibodies.

In our next article, we’ll cover our outlook for an effective vaccine, which we believe will be necessary to end the pandemic.

/author-service-images-prod-us-east-1.publishing.aws.arc.pub/morningstar/558ccc7b-2d37-4a8c-babf-feca8e10da32.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/10-04-2024/t_e6175f671cee439d9180e460f6081183_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/LE5DFBLC5VACTMC7JWTRIYVU5M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/PJQ2TFVCOFACVODYK7FJ2Q3J2U.png)

:quality(80)/author-service-images-prod-us-east-1.publishing.aws.arc.pub/morningstar/558ccc7b-2d37-4a8c-babf-feca8e10da32.jpg)