Discounts Remain in Multi-Industrials

We find several undervalued stocks and one compelling bargain.

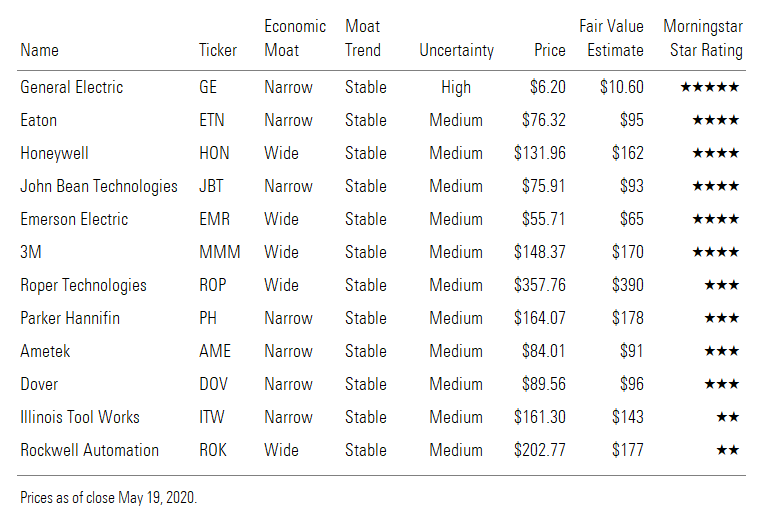

Predicting a market bottom is a fruitless exercise. In our view, the central tenet of all intelligent investing is a stock’s margin of safety, which maximizes preservation of capital through all market cycles. Although the bands of uncertainty have widened amid the global pandemic, we believe we can recalibrate and price securities in a base-case scenario based on historic economic cycles, medical data, government intervention, and market commentary from informed participants. After the late March rally, we find several discounted stocks and one compelling bargain. In this piece, we put portions of our U.S. multi-industrials coverage into four buckets: cash compounders, traditional quality, dividend aristocrats, and beaten-down value. Our favorite stocks in these respective categories are Roper Technologies ROP, Honeywell HON, Emerson Electric EMR, and General Electric GE.

Bumpy Recovery, but Short-Cycle Businesses Return First The average discount in our U.S. multi-industrials coverage is 10%, compared with the Morningstar market fair value discount of 5%. Even so, this is a category that is arguably better positioned to benefit from a recovery, given the business-to-business mission-critical services it provides. 2020 will be a terrible year for industrial earnings, but we believe investors should look past this year when assessing underlying value.

Much market commentary centers on whether the economy will recover in a V-shaped, U-shaped, or l-shaped pattern. Our assessment is more end-market-specific. For instance, John Bean Technologies’ JBT food automation business typically sees a greater return to growth in the second year after a downturn. Short-cycle businesses (that is, an order is placed and quickly filled) like 3M MMM, Illinois Tool Works ITW, and Rockwell ROK, as well as approximately 60% of Honeywell’s portfolio, tend to fall quicker in a downturn. Yet, short-cycle businesses bounce back quicker than the rest of the market in a recovery. Emerson’s instrumentation, aftermarket, and discrete businesses fall into this category as well.

With large backlogs that can take several years to burn through, long-cycle businesses afford management teams greater visibility, but new orders will fare worse at the start of a recovery. This includes most of General Electric’s business, 40% of Honeywell’s business, Emerson’s final control and systems businesses, and portions of Ametek’s AME portfolio that overlap with GE’s markets in both aerospace and power. Intuitively, it’s far easier to sell Post-it notes than it is to sell a LEAP aircraft engine at the outset of a recovery. Customers frequently delay orders during the early portions of a recovery in long-cycle businesses.

Given China’s national mobilization efforts, we wouldn’t be surprised to see a V-shaped recovery in that nation’s economy. This could benefit companies like 3M and Emerson, which have significant operations in China, at what we think is about 10% and 12% of sales, respectively. Since the cadence of a recovery ultimately affects the discounting of cash flows, we think it’s especially critical to remain disciplined with a strict margin of safety to maximize preservation of capital.

We looked to several reference points in the past to model our 2020 bottom-up assessment on a segment and, depending on disclosure, end-market basis. First, we looked at prior economic shocks and public health emergencies, including Sept. 11, 2001, the 2003 SARS outbreak, the 2008-09 Great Recession, and the 2014-16 Industrial Recession. While this was a starting point, our analysis reveals some end markets will perform worse while others are likely to perform better than prior periods of economic disruption.

For instance, in March, the International Air Transport Association forecast that global revenue passenger kilometers (a measure of commercial global air travel demand) will fall 48% year over year by year-end. That’s by far the biggest drop in air travel since data is available dating back to 1978. Using prior crises as a reference point is mostly irrelevant, given that the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on global air travel is multiples worse than either Sept. 11 or the Great Recession. It is likely to take years to recover lost economic output, since a sharp V-shaped recovery would require an unlikely 100% year-over-year recovery in 2021.

Part of the challenge of using prior recessions is that multi-industrials are inherently portfolio businesses that frequently resegment their operations and acquire and dispose of businesses. There are natural limitations to using through-the-cycle organic compound annual growth rates for those businesses, particularly since some critical businesses were acquired in the private market. This pandemic-related recession is also different because there were several quarters of slowing growth before the Great Recession. Emerson was already planning for a no-growth scenario, for instance, and worked to preserve margin and boost liquidity, including reducing inventory to preserve cash.

Our projections also assume that a coronavirus vaccine will be available in 12 months (in a bull-case scenario) to 18 months (in a base-case scenario). We assume that such a vaccine could be distributed en masse, without the potential for what’s known as “immune enhancement,” whereby a vaccine effectively weakens a person’s response to the virus. In the interim, based on our survey of medical literature and some channel checks, some therapeutics display promising results. We would not be surprised to see a resurgence of cases in the fall and winter months and subsequent government intervention, in a base-case scenario, but with access to therapeutics.

Cash Compounders: Wonderful, Asset-Light Businesses at Fair Prices Cash compounders typically generate high returns on tangible assets, require little capital to maintain competitive positioning (which allows them to enjoy free cash flow in excess of GAAP earnings), and compound intrinsic value through value-accretive acquisitions (after addressing internal reinvestment needs). Cash compounders are rarely cheap in a traditional sense, but they're advantageous in a portfolio because intrinsic value tends to grow, which potentially minimizes the need for portfolio turnover. While they tend to trade down with the category in economic downturns, we think this creates potential buying opportunities as the divergence between price and value tends to appreciably widen during these periods. That's particularly the case since arguably most of their value lies in future acquisitions, which are easier for management in an environment of battered valuations.

Roper Should Increase Earnings and Expand Multiples in Mix Shift Roper Technologies may be the most unusual business in our multi-industrials coverage because labeling it an industrial is a misnomer. Roper is largely a software business (about 55%), with some healthcare and materials testing, utility, and other stable end markets, as well as about 20% of cyclical sales exposure (split 11% and 9% between industrials and energy). This causes what we believe are egregious errors in valuation, particularly given Roper's relatively high multiples. There are two major issues with relying on a simple average multiple to earnings when valuing Roper: GAAP earnings materially understate Roper's earning power, and Roper will increasingly become more of a software business as it exclusively purchases these types of businesses as part of its acquisition strategy.

Roper is an inherently better business than any other multi-industrial we cover. We like businesses that gush cash. Roper’s businesses frequently don’t own their own software infrastructure, which makes the company incredibly asset-light. GAAP earnings understate Roper’s earning power because the company’s software businesses are paid ahead of time, and these payments are booked as deferred revenue because Roper receives cash before rendering services. Although deferred revenue is classified as a liability, we think of it as Roper’s strongest asset. Large quantities of deferred revenue allow Roper to enjoy negative working capital of about 4%-5% of revenue. About 60% of Roper’s business is built on recurring revenue, which frequently boasts customer retention rates in excess of 95%. These cash payments are protected by several moat sources, including switching costs in the company’s application software business and network effects in its network software business. Most of Roper’s software businesses are boring businesses in niche markets with small total addressable markets. These businesses typically increase their top lines at a mid- to high-single-digit organic CAGR.

A common concern is Roper’s penchant for buying businesses from private equity. Private equity firms generally need an exit, since the reward from software business with a mid- to high-single-digit top-line CAGR isn’t going to suffice for them. High returns are nice, but the best businesses can invest their cash flow at incrementally higher rates of return. Roper measures this through its own iteration of return on tangible assets, which it calls cash return on investment, or CRI. The formula takes net income plus depreciation and amortization less maintenance capital expenditures all over gross fixed assets and net working capital. CRI is highly correlated with long-term stock market returns. The company typically claims the R-squared between the two variables ranges is 94%-98%.

To invest in businesses at incrementally higher rates of return, Roper only considers targets that are additive to CRI. On the price side of the ledger, when it considers an acquisition, Roper values its stock by both including and excluding the effect of the acquisition. The difference in outputs is the incremental value to Roper, and the company consistently pays a fraction of the difference. Acquisitions constitute about one third of the value in our model, implying that relying solely on our organic assumptions would take us toward the bottom end of S&P Capital IQ consensus price targets.

Another common concern is that Roper is starving its businesses for capital. However, we estimate that capital expenditures required to maintain competitive positions generally only amount to 1% of sales, with the remaining portions of capital expenditures funded toward value-accretive growth opportunities. Most of the true capital expenditures are expensed in the form of research and development, which are typically about 6% of sales and toward the top end of our industrial coverage (most industrial companies typically spend 2%-3% of sales on R&D).

An addition concern is Roper’s growth runway. The law of large numbers eventually gets in the way of even the best-run companies. However, we believe Roper should be able to increase free cash flow (cash flow from operations minus capital expenditures and capitalized software) about 14% over the next seven years, in line with its historical experience. Roper says it easily has a 15-year growth runway ahead, which we think is doable assuming a rolling four-year allocation of capital to acquisitions at $7 billion, followed by $8 billion, and $8.5 billion, which we amortize over our 10-year explicit forecast (less the remaining 2 of these 12 years).

One final concern is pricing. Roper doesn’t move its executives from business to business. We think this is a positive because executives are allowed to run their businesses with nearly complete autonomy, in their circle of competence, with the customers they know best. However, Roper does have group executives who help each business executive think about CRI. This dynamic specifically comes into play with pricing. Roper coaches each of its business executives not to try and take maximum price each year (which we interpret as management’s emphasis on the lifetime value of a customer). On the flip side, after Roper purchased government contracting software business Deltek, company representatives were onboarded and taught to think about getting paid up front in exchange for a modest discount on price. This was the opposite case under Deltek’s prior management team, which would trade and extend payment terms in exchange for incrementally better pricing--a poor CRI decision.

Few Alternatives in Niches Ametek Dominates Ametek is a cash compounder that heavily relies on acquisitions to drive earnings growth, but its strategy differs from Roper. Ametek typically acquires companies that are in adjacent markets to its already existing end markets, reasoning that it's preferable to invest in the businesses it knows best. Recurring revenue is a nice byproduct of some more recent acquisitions, but from what we gather, not having recurring revenue is not going to derail an Ametek acquisition.

Ametek’s businesses have concentrated market shares and are typically strong oligopolies. Market shares for its broad portfolio are 30%-plus, which is very strong for our industrial coverage (and some markets are even duopolistic). Ametek’s niches are strong because there are few alternatives in the high cost of failure markets Ametek competes in, which, from a Porter’s five forces standpoint, translates to heavy switching costs. One example is Ametek’s germanium-based detectors, which are used to detect nuclear material at various national entry points (and are a superior solution to silicon-based detectors). Another example is Ametek’s Zygo, which manufactures instrumentation and mission-critical componentry used in the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory. That observatory was instrumental in the detection of gravitational waves, which ultimately helped prove Einstein’s theory of general relativity. Zygo’s equipment was integral to this Nobel Prize-winning effort in 2017.

Ametek’s business is highly innovative. The company allocates 5% of sales on research and development. Unlike many of its industrial peers, however, Ametek generates greater-than-inflation pricing power (typically 20-30 basis points greater than inflation, but as high as 50 basis points more recently). That’s atypical as most industrials generally only have sufficient pricing power to offset their material and other costs, but typically after a lag effect of a couple of quarters. We think this speaks to the strength of Ametek’s intangible assets.

Ametek’s ability to extract significant cost synergies from its targets is another key difference with Roper, since Roper rarely attempts to get a step-up in margins after an acquisition, which is far harder in a software business. Ametek frequently improves its targets’ margins from the low teens to the lower 20s on an EBITDA basis. Most targets have done a poor job globalizing their supply chains, which presents an opportunity for Ametek. When Ametek onboards its acquisitions, it introduces a whole set of suppliers around the world in low-cost regions that it has prequalified to do certain tasks like circuit board construction, precision machining, and product casting. Since material costs are frequently a niche instrumentation company’s highest-cost input (about 20%-25% of its costs), this allows Ametek to make a near-immediate uplift to a target’s margins.

While acquisition risks can never be entirely obviated, we think they are minimized with a company that regularly engages in M&A activity as part of its strategy and culture. Ametek has done a good job of maintaining returns on invested capital, including goodwill, in the low teens, and though we think that number will drop to the high single digits this year, in a normalized environment these levels of returns comfortably exceed our estimated cost of capital for the company of 8.5%. The company has never taken a write-off of any of its businesses, so it has an extensive record of success. Ametek’s success is the result of its disciplined acquisition strategy, which demands that targets achieve a 10% ROIC within three years. While Ametek aims to double earnings per share every five years, as it has in the past, what matters to us is that it’s able to do so at value-accretive prices.

Traditional Quality: High ROICs in Not-So-Old-World Manufacturing Like cash compounders, the companies in this category tend to have very strong economic moats around their businesses; we assign wide moat ratings to both Honeywell and Rockwell Automation. They have good balance sheets and quality management teams making solid capital-allocation decisions. In contrast to cash compounders, however, these companies rely less on regular acquisitions to drive earnings growth. They tend to have large installed bases of equipment with significant higher-margin aftermarket revenue that can last decades into the future, which explains their durability and high returns on invested capital.

Of the two stocks we mentioned, we like Honeywell better and plan to write more about it in a future piece. Despite its significant exposure to the oil and gas as well as aerospace end markets (about half of all revenue), we prefer the stock based on its valuation. We expect that portions of Honeywell’s business, like warehouse solutions, may see a quicker recovery than industry peers, particularly given the strong trend toward e-commerce and current social distancing norms. Honeywell’s balance sheet is also among the strongest of all industrial companies we cover, and we believe earnings may be more resilient than the market appreciates, given the company’s ability to liquidate its balance sheet. We suspect it may have bought back additional stock at value-accretive prices during the sell-off in March. The company was also able to expand segment profit margins despite the precipitous drop in the price of oil during the height of the Industrial Recession.

Rockwell is at the forefront of what it calls the convergence of information and operation technology. Many companies see automation as the final frontier for driving efficiency gains and greater throughput, and technology is becoming a more integral part of this change. We think Rockwell has smartly chosen to cede control and split potential upside by exploring partnerships with PTC up the automation stack (it owns just under 9% of PTC) and with Schlumberger across the automation pyramid. Rockwell’s traditional sweet spot is in discrete automation (small parts made into bigger components, as seen in automotive and semiconductor manufacturing) as opposed to process automation.

Aside from more recurring revenue from these new initiatives, which should help ameliorate cyclicality, the joint ventures help with the breadth of Rockwell’s portfolio offerings. We think it gives Rockwell somewhat of an edge when selling to customers that appreciate a one-stop shop in certain hybrid end markets, which combine characteristics of both discrete and process automation.

From a strategic standpoint, trading control for greater speed to market and risk mitigation is also a favorable dynamic, in our view. Rockwell doesn’t have to commit large amounts of capital to obtain wins; hence its superior return on capital profile. This selling edge is important, given how expensive the equipment is. Once Rockwell is in a factory, the aftermarket tends to last 20-30 years, which makes our wide-moat assessment all the easier. The company has made some astute bolt-on acquisitions like MagneMotion in 2016, which gave it access to end-market agnostic equipment that is modular and can be independently controlled.

Dividend Aristocrats: Consistent, Predictable Income in Uncertain Times Dividend Aristocrats tend to increase their dividends on an annual basis for decades. Four companies we cover have done this for over 60 years: Emerson, Dover DOV, 3M, and Parker Hannifin PH (though we put Parker Hannifin in another category, given its high leverage). ITW has accomplished this for over 50 years. While it hasn't increased its dividend annually for decades, we think narrow-moat Eaton ETN is similar enough that it could be placed in this category as well. Its dividend has grown at about an 11% CAGR during the most recent 10-year period, and its 3.7% dividend yield places it in the top quartile of the multi-industrials companies we cover. Aside from the recent sale of lighting, that company should see fundamental improvements to returns on capital, in line with its historical highs in the low to mid-teens. There are two catalysts in Eaton's stock that we think the market fails to appreciate: improving decremental margins relative to the Great Recession, which we think should total 25%-30% (at worst), and the divestment of its hydraulics business, which we're confident will close and which Eaton sold at a far better than expected multiple. Prices for dividend stocks have generally risen very high as investors chase yield in a low-interest-rate environment, but that's not uniformly the case.

ITW, for instance, is a very well-run company. It’s willing to sacrifice some organic growth for margin and ROIC preservation, which helps it consistently increase earnings. The company has institutionalized the Pareto principle throughout its operations and has aggressively eliminated underperforming stock-keeping units as part of its product line simplification initiatives. Despite our admiration for the company, its results simply don’t justify its valuation, and we hold off on assigning a wide moat given that it lacks the decades-long aftermarket mix commonly found in aerospace and industrial automation (nearly two thirds of ITW’s sales are in equipment). We attribute the quality of its returns on capital to exemplary stewardship as opposed to any inherent moat source.

Dover is another high-quality stock whose potential we think the market has largely recognized. The company pulled its earnings guidance, and despite the cloudy earnings environment and the suspension of further stock repurchases, we think that the dividend is safe and that its unbroken chain of increases will continue. Of all Dover’s lines of business, we’re most bullish on retail fueling. We think gas stations are an essential service. The price of oil has offset recent traffic volume weakness (which helps drive record-high margins), and store ticket purchases in the United States are higher as customers stock up on essential purchases. We think EMV (chip card) trends should stay strong at gas stations over the next few years, and we continue to model mid-single-digit growth in retail fueling, even when baking in a near-term slump in demand. We think the impending liability shift in October 2020 will continue driving demand in the U.S. and expect mid-single-digit-plus growth in the company’s services and software business. We also believe there is a secular shift away from public transport toward private transportation, which should further help these trends.

Resilient Business Model With Catalysts Remains Core to 3M Thesis While 3M doesn't afford investors the greatest opportunity for large capital gains, we do believe it offers investors safety of principal, with a forward dividend yield of nearly 4% in a discounted stock, in a world of near-zero interest rates. After we reviewed the impact of COVID-19 on 3M's business, we believe the reduction in fair value is materially less than what 3M experienced during the Great Recession.

First, we think the surge in demand for 3M’s N95 respirators is a decent catalyst in the stock that the market fails to appreciate. This surge adds about 4% of the value we ascribe to the company. For respirator sales, we assume 3M sells each unit at an average price of about $0.70 and further assume a gradual ramp in production at a rate of 2 billion units annually from 1.1 billion. We believe all will sell, given current supply constraints (90% of N95 mask sales were previously directed toward industrial applications, like construction). We then deduct the sales benefit from 3M’s prior production rate (about half of the current 1.1 billion).

We also expect to see some modest benefit from cleaning solutions, including scrubbers and wipes frequently used on kitchen and bathroom surfaces (mostly sold through 3M’s Scotch-Brite brand). While we expect 3M will no longer return to growth, as it intended at the beginning of the 2020 when management issued guidance, we’re only modeling a 0.3% decline in its top line. That said, we think value-accretive repurchases toward the bottom of the crisis could add about $4 per share to our valuation. As for 3M’s PFAS liability, we maintain that bears’ targets imply an ultimate liability of over negative $20 per share versus negative $6.50 in our valuation. The difference between other price targets and our fair value estimate, we believe, primarily lies in the PFAS overhang.

Even if we’re wrong in our growth assumptions, we think our earnings power value supplementary analysis is useful. Earnings power value measures the cash flow that can be distributed to shareholders in a no-growth scenario, properly adjusted to account for maintenance capital expenditures (which we estimate are about one third of total capital expenditures) and the amount of spending a competitor would need to replicate 3M’s research and development capabilities. At current prices, investors are getting most of the growth in 3M from these levels for free.

Emerson's Margins Better Thanks to Aftermarket Revenue Mix We largely agree with CEO David Farr's commentary during Emerson's fiscal second-quarter earnings call that the economic activity in industrial end markets will not return in a V-shaped pattern, except for China. The takeaways from the results are that (1) sales and earnings will be mostly in line with our revised expectations after the impact from COVID-19; (2) automation organic sales will be down 7% year over year at the midpoint, worse than we expected; (3) commercial and residential solutions will be down 10% at the midpoint, appreciably better than we expected; (4) the downturn will follow a similar pattern to prior recessions, with the exception that a no-growth environment immediately preceded the economic fallout, while the recovery will take longer; (5) margins are more resilient, given higher levels of aftermarket (parts and service) revenue than in prior cycles at 60% of overall sales (versus a hair above 40% during the Great Recession); and (6) minimal supply chain disruptions are expected, given years' worth of supply chain regionalization efforts.

In February, Emerson provided 2023 targets that included a 3% organic growth target for 2019-23. With full-year 2020 guidance of negative 8% year over year, and perhaps an additional three quarters of negative to at best flat growth, we think it’s a stretch to get to that 3% number. We model just under 2% underlying sales growth from 2019 to 2024 (which even bakes in an additional year of a recovery). Given the dearth of organic opportunities to put capital to work in the near term, we doubt Emerson will manage to deploy all $3.4 billion it originally anticipated in the pre-COVID-19 world through 2023. We model $3 billion during our five-year explicit forecast through 2024.

In terms of challenges of selling to customers in this environment, some end markets are high touch points, which is especially challenging given that automation equipment is inherently expensive. A sale can be difficult, given the need to demonstrate to customers that they can get a day-one return on their investment from new equipment installs. Certain end markets particularly prefer face-to-face contact, including power, chemical, and wastewater treatment. Nevertheless, Emerson is slowly implementing more digitization in its sales presentations. We also hear that in certain hybrid markets like food and beverage and life sciences, customers prefer a one-stop shop, particularly given the inherent complexity of their operations. Longer term, we still think Emerson Electric will benefit from the lack of available skilled labor in the U.S., wage inflation, and the related need to drive increased productivity amid customers’ reduced labor force.

Beaten-Down Value Stocks With Weaker Balance Sheets Could Be Buried Treasure We place General Electric, Parker Hannifin, and John Bean Technologies in this category. Their disproportionately large commercial aerospace exposure has now become a double-edge sword. Their problems are exacerbated by weaker balance sheets after years of using leverage to make acquisitions (although in JBT's case, we think purchases have been mostly value-accretive and the debt burden is far more manageable). These companies traded further down than the rest of the category during the March sell-off and lagged in the subsequent rally. We think the market correctly recognized the inherent risks in these businesses. However, we believe their stock prices overshot economic reality to the downside.

Parker Hannifin, for instance, is an inherently cyclical stock, with about 18% of sales in aerospace, 5% in automotive sales, and 2% of sales from oil and gas (with about 65% of its exposure in upstream-related assets). Parker Hannifin took on significant debt with what we believe were slightly value-dilutive acquisitions in Lord and Exotic Materials. We expect net debt/EBITDA will exceed 4 times, despite the company’s confidence that it can bring the ratio down to 3.6 times on a gross basis.

We recommend investors require a wide margin of safety in these stocks. Since both JBT’s and Parker Hannifin’s shares have somewhat recovered, we recommend the shares of narrow-moat General Electric to investors with strong stomachs and lots of patience.

GE's Grounded Shares Will Return to Being Ready for Takeoff Our GE thesis is an all-out bet on CEO Larry Culp and his ability to turn around the company's vital, mission-critical global assets. That just got significantly more difficult with the global pandemic, however. In contrast to when we last made our 5-star call in December 2018, selling off assets will no longer help close the price/value gap. As a result, sum-of-the-parts valuation, which we heavily relied on then, is less useful going forward. GE will have to prove it can produce and eventually improve on its industrial free cash flow with the assets it has in place. Nevertheless, despite formidable headwinds, we think GE trades at a compelling valuation.

The commercial aerospace environment faces rapid degradation. As a result, we cut our adjusted earnings per share estimates for 2020, 2021, and 2022 and forecast 2020 industrial free cash flow to be about negative $700 million (which we believe is directional). We also believe GE won’t come close to hitting its intended net debt/EBITDA target of 2.5 times (we estimate 5.9 times by year-end 2020) as set by the rating agencies to prevent a credit downgrade. Therefore, we already model a higher cost of debt in our GE model.

Aviation is a key part of the GE story going forward, given its disproportionate impact on the company’s portfolio. Commercial aerospace is inherently an extremely long-cycle business; it typically takes GE about seven years to burn through its backlog. While engine orders can be canceled, canceled engines are typically moved by airframers to other program customers. In GE’s case, the narrow- and wide-body aircraft markets are duopolies with Pratt & Whitney and Rolls-Royce, respectively. Replicating GE’s installed base would take decades, given its massive scale, technical expertise, and intellectual property, as well as its long record of success.

Properly valuing this razor-and-blade business should take into account the life of an engine program for decades into the future. Given what we see as little chance of competitive disruption, the main variable we examine is demand. We think 2020 demand will be disastrous and believe a V-shaped recovery is highly unlikely. For demand to recover to current levels, assuming year-one IATA forecasts hold, we would have to assume an increase of approximately 100% in the first year of a recovery. Complicating matters is what we anticipate will be overcapacity for the next few years, given years of increasing production rates from companies trying to keep up with demand during the commercial aerospace boom. Other issues include pricing pressures.

Nonetheless, we believe the recovery may be better than what analysts forecast. When we were initially re-examining the data, we hypothesized a lethargic recovery. Our thinking was most of the flying public would refuse to board an aircraft without a vaccine, according to the time frame we detailed in our macro assessment. We also inferred that efficacious therapeutics would be insufficient to alter this risk-reward assessment. A few data points stood out to us, however. While economists at IATA saw this as a potential cause of concern, we considered it a positive data point: In an April 2020 survey conducted in 11 countries, only 8% of those surveyed stated they would wait a year or so before flying (within the outer bands on an approved vaccine), and only 4% stated they would not travel for the foreseeable future. Three fourths of respondents said they would be willing to fly between one month to six months, with 14% saying they would be willing to fly immediately. While load factors (a measure of utilization) probably won’t return to normal levels for some time, given social distancing norms, we found the data encouraging nonetheless.

Furthermore, we don’t believe COVID-19 will permanently alter global air travel in a manner that significantly hampers long-term growth. Aside from general urbanization trends, which give developing nations’ citizens greater access to airport terminals, the key variable we look at is the growing middle class. Most global air travel demand comes from developing nations like China, and while the International Monetary Fund predicts that China’s real GDP will grow only 1.2% in 2020, it should grow 9.2% in 2021.

According to the Brookings Institution, the global middle-income class is set to expand consumption at an average rate of 4% over the long term, with tourism and transport as areas that are ripe for spending. According to World Bank data, the middle-income class in China alone is expected to grow to greater than the population of North America and Europe combined within 10 years. And the rise of urbanization in nations like China translates to over 10 times the number of cities in the U.S. with a population of greater than 1 million (we count about 117 in China and about 46 in India). We take all these data points as support that global commercial air travel can still grow 4%-5% over the next two decades, despite this severe economic shock. Even if it’s at the lower end of the range, that’s better than the growth we typically see in other industrial end markets.

Furthermore, given the secular shift away from wide- and toward narrow-body aircraft as jets like the Airbus’ A321XLR can now travel longer distances, we like GE’s positioning, given its massive installed base. We believe this gives it a huge competitive advantage in the higher-margin aftermarket. It also allows GE Aviation to escape the margin pressure in Pratt & Whitney’s commercial aerospace business, given Pratt’s comparably far smaller installed base (a loss-leading engine is going to have a bigger impact on Pratt’s business). We think GE Aviation aftermarket sales will recover faster than original equipment sales by 2022, particularly since aircraft and their engines still need to be in good working order and repair. The CFM joint venture, of which GE is a 50% owner, boasts the largest installed base in the narrow-body space. It’s also the youngest installed base, since roughly 62% of CFM’s fleet has seen one shop visit or less. We like GE’s positioning here since we think narrow-body aircraft will recover more quickly than wide-body jets.

We also don’t believe GE’s current situation will last forever. To get to sell-side bears’ targets, one would have to assume GE Aviation is now worth $30 billion on an enterprise value basis, which is simply divisors away from economic reality (between $80 billion and $100 billion) in anything but the most extreme of fire sales. We think GE should still be able to hit a high-single-digit free cash flow yield sometime within years three through five of our model. The fundamental improvements Culp and his team are driving on the ground are heavily obscured by the inheritance taxes related to former CEO Jeff Immelt’s ill-priced purchase of Alstom, which have totaled an annualized rate of $1 billion-$2 billion in recent years. We think those will dissipate completely by 2023. While GE will never regain its former stature, we think it has a viable path to become a leaner, well-run, and more focused conglomerate.

General Electric, Eaton, Honeywell, John Bean Technologies, etc =.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/MX3XFKYTXVG2RGAL3JZKVC526Y.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZPLVG6CJDRCOTOCETIKVMINBWU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/Z34F22E3RZCQRDSGXVDDKA7FGQ.png)