Don’t Believe What You Read About Target-Date Funds

The latest missive from Bank of America is no exception.

A Tempting Target

The problem with target-date research is that unless its conclusion is dramatic, the study will not sell. Target-date funds, however, yield no drama. They are dull by design. Here and there, a target-date series might flop, but the group cannot.

That does not stop researchers from making the effort, though. A recent instance is last week’s client note on target-date funds, issued by Bank of America. As I am not one of the bank’s customers, I did not receive the dispatch. However, this week’s Barron’s summarizes the note’s findings, in an article called “Target-Date Funds are Popular. But Mediocre Returns and Other Risks Warrant a Closer Look.”

Per Barron’s, target-date 2040 funds have “lagged the S&P 500 by a compounded annual average 2.4 percentage points over the past 28 years, returning 750% in total over the time frame, versus 1,494% for the broader market. The funds also trailed a balanced 60% stock/40% bond allocation, which posted 866%.”

Those numbers are accurate, and they sound damning. In that same spirit, though, I offer another comparison. “A diversified portfolio that consisted of 70% U.S. equities and 30% foreign stocks lagged the S&P 500 over the past 28 years, returning 927% over the time frame, versus 1,494% for the index.” Would that statement persuade you that the diversified portfolio had been poorly managed?

Perfect Hindsight

It does not convince me. The rearview mirror indicates that the optimal foreign-stock allocation is the one with the highest past returns, but the windshield offers no such guarantees. Consequently, investment researchers are deeply divided. For example, while Jack Bogle (in)famously shunned foreign stocks, the company that he founded, Vanguard, suggests that investors put 40% of their equity assets into foreign securities. Whatever your view, you can find an expert who agrees.

My point? It is easy to make allocation choices look silly in hindsight, particularly by compounding the results (a rhetorical device that I know well, having frequently used it myself; as my father liked to say, you can’t con a con artist). Any diversified portfolio may be so chastised, since every one of its assets will trail the top performer, except the top performer itself.

Three Questions

What matters are the answers to the following queries:

1) Can the investment’s strategy be justified?

2) Was the investment competitive with the realistic alternatives?

3) Did the investment succeed by its own measures?

Target-date 2040 funds began by placing about 90% of their assets in stocks. Over time, they have gradually decreased that amount, which currently averages 77%. Foreign stocks have consistently made up one third of their equity positions.

There are two possible critiques of this approach. One is that the target-date funds overindulge in equities. After all, few endowment funds invest so heavily in stocks. The other possible charge, of course, was that the international-stock allocation has been excessive. Bank of America’s report discusses the second item, but it omits the first. That is unreasonable. If one is to conduct hindsight analysis, address both the winning and losing decisions.

Against the Competition

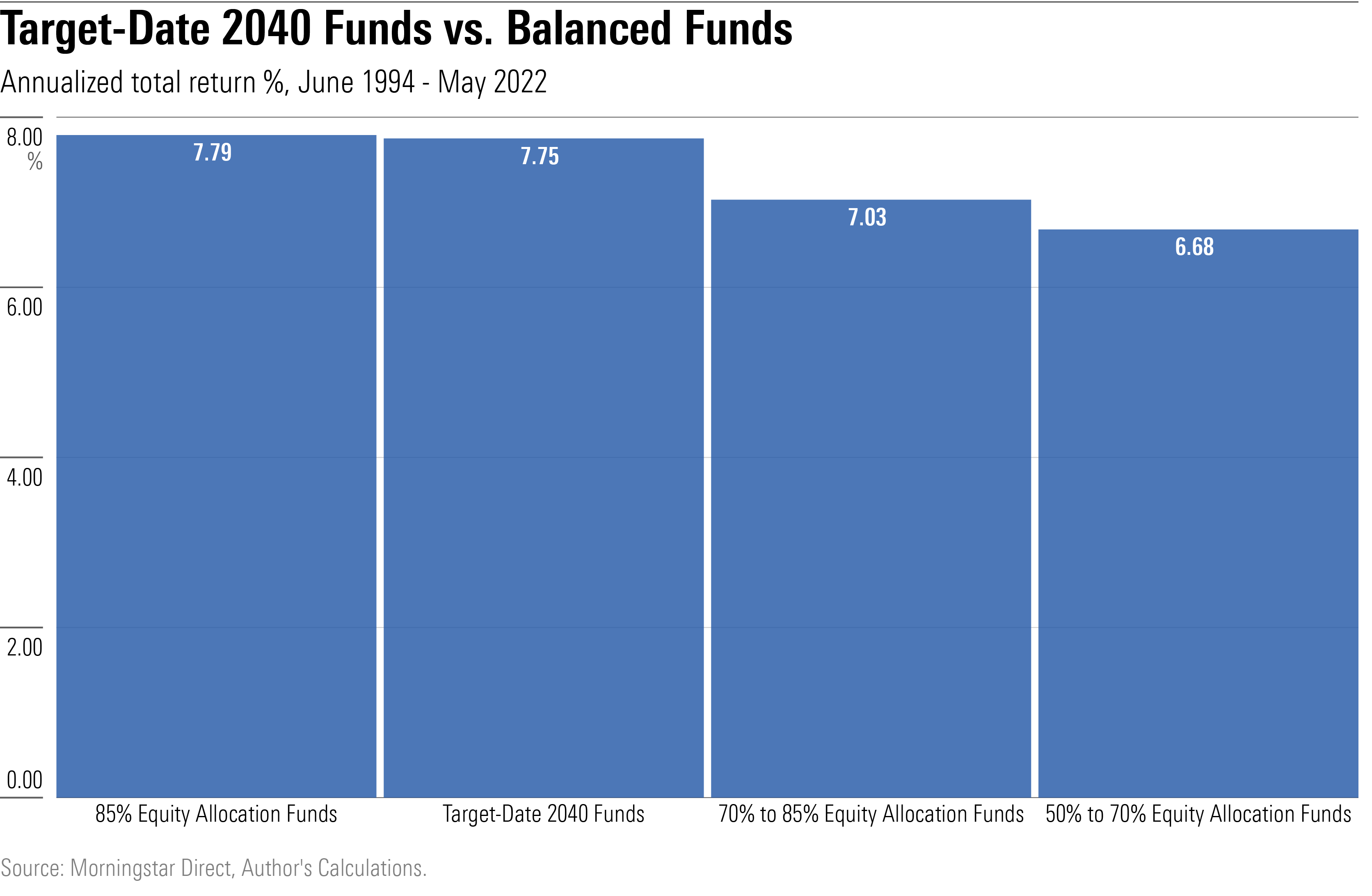

The second question that I posed addresses practical rather than theoretical considerations. Would target-date 2040 fund shareholders have fared better if they invested elsewhere? The answer is no. The following chart shows the performance of target-date 2040 funds since their 1994 inception against three categories balanced funds, which unlike the 60/40 benchmark cited by the Bank of America paper, also contain foreign securities, cash, and ongoing expenses.

The 2040 funds look fine when compared with the existing alternatives. They matched the returns of allocation funds that consistently invest 85%-plus of their assets in equities, while modestly outgaining more-conservative allocation funds. On a risk-adjusted basis, as measured by the category’s Sharpe ratio, target-date 2040 funds placed second among the four depicted categories. Yet I do not recall reading white papers about the deficiencies of balanced funds.

Against Itself

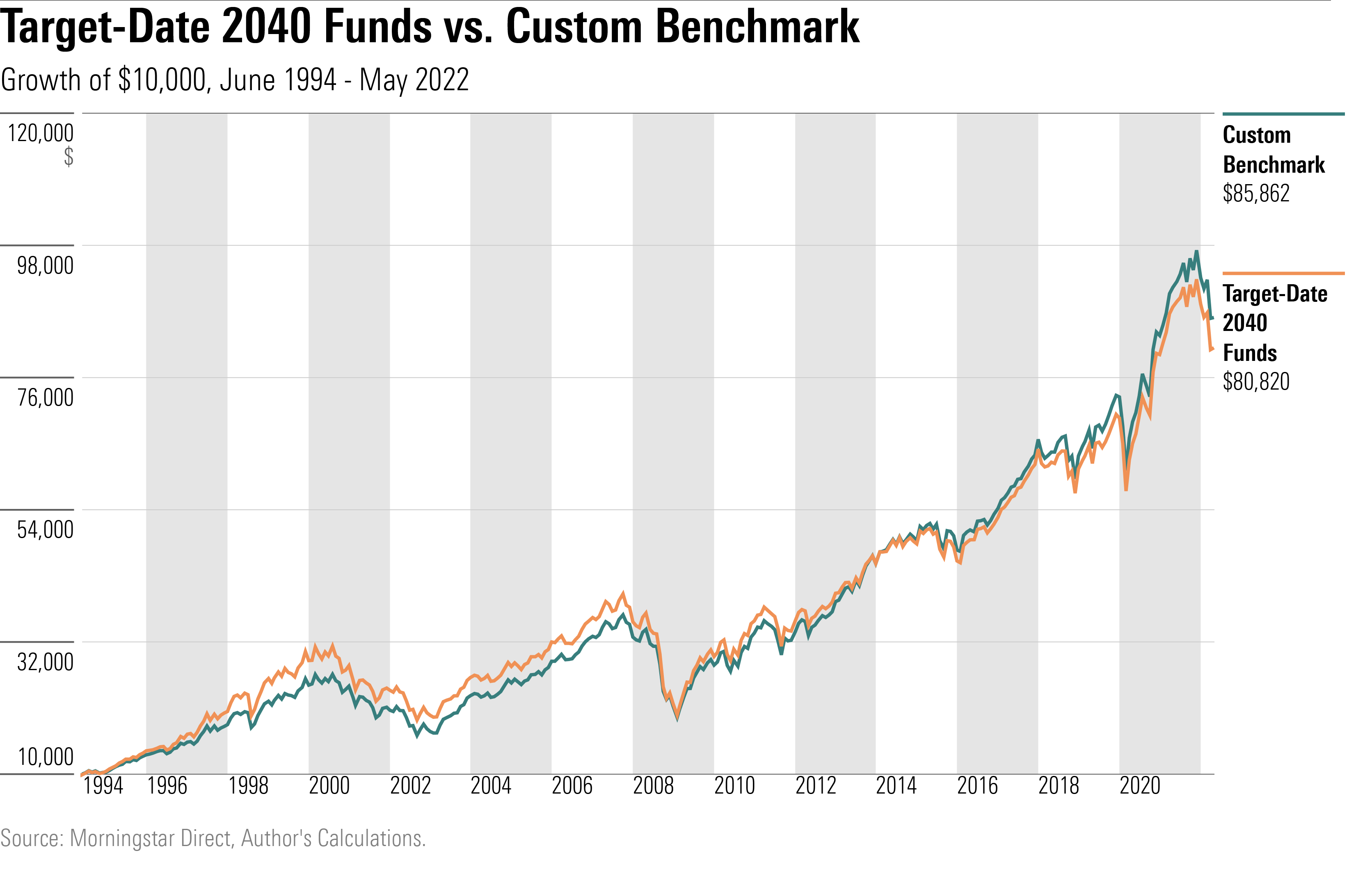

An investment can fail in other ways besides asset allocation. It may also be ineptly implemented. To test whether target-date 2040 funds botched their assignments, I created a custom benchmark that duplicated exposures to four asset classes: 1) U.S. equities, 2) foreign equities, 3) bonds, and 4) cash. I then compared the benchmark’s total returns to that of the category average.

(For reference, I separated the 28-year history into four seven-year periods, determining the average asset allocations for target-date 2040 funds for each period. I then used those figures to create the custom benchmark, which was constructed from four indexes: 1) Morningstar U.S. Market, 2) MSCI EAFE, 3) Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond, and 4) Bloomberg U.S. Treasury Bills.)

An excellent showing for the target-date 2040 funds. They trailed the custom benchmark by only 0.23 percentage points per year, which is less than their expenses. To be sure, that result does not necessarily indicate that their managers selected securities adroitly. It may instead be that indexes imperfectly match the funds’ investment universes. But the outcome certainly does not imply problems.

The Active-Manager Myth

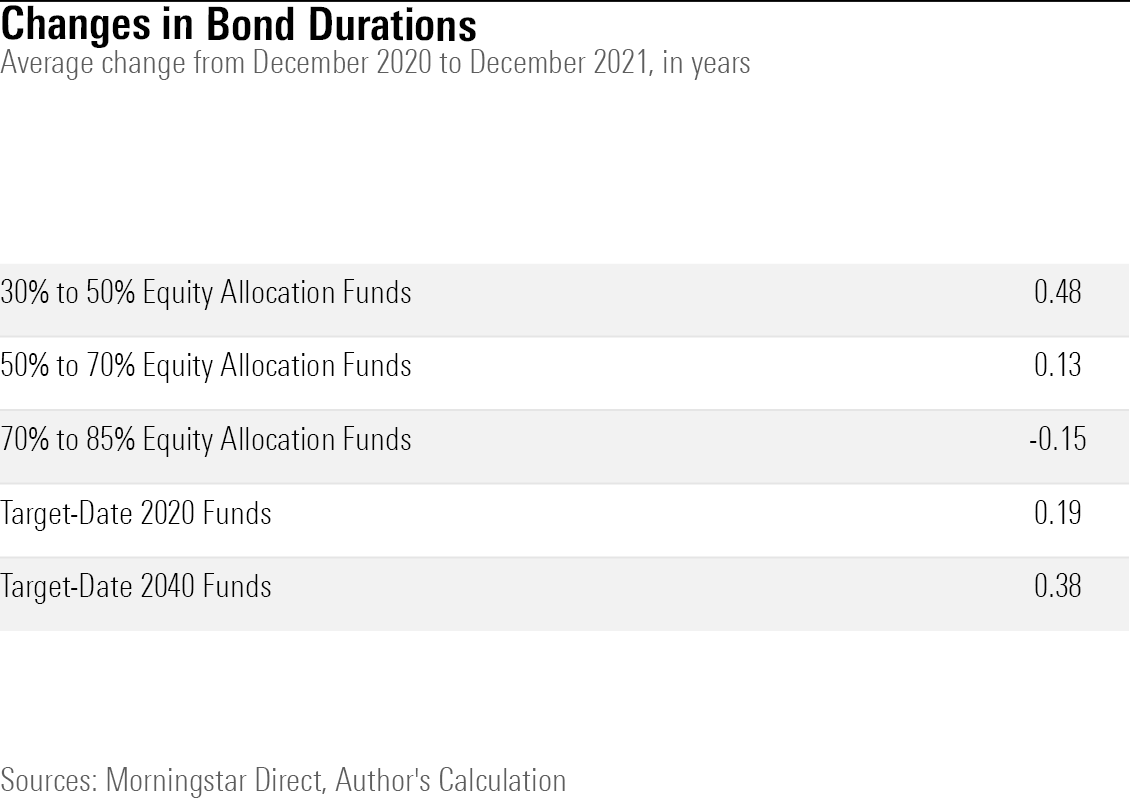

A final complaint from Bank of America’s analysts was that target-date funds did not adjust their investments in response to current market conditions, by not lowering their bonds’ durations—meaning their interest-rate sensitivity—as yields have increased. Thus, stated Barron’s, “as many bond investors have been shortening durations,” target-date funds have suffered from staying the course.

Such is always the criticism of strategic portfolio managers—that they do not respond to changing market conditions. Neither, unfortunately, do most tactical portfolio managers. To be sure, they adjust their investments. But that does not mean that they do so accurately. For every manager who foresees the next movement in interest rates, there is another who expects the opposite.

Below are the recent changes in the average bond durations, expressed in years, of target-date 2020 and 2040 funds, compared with the results for the three previously mentioned balanced-fund categories. The measurement period consists of the 12 months from December 2020 through December 2021, when inflation went from dormant to resurgent. Once again, target-date funds have behaved no differently than their rivals.

But of course, the outcome could scarcely have been otherwise. If the average active mutual-fund manager could forecast changes in bond yields, or for that matter stock-market trends, the index-fund revolution would have perished in childhood. The implication that target-date funds have failed where others have succeeded is a myth. As are the papers that purport to show such results.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1dc0e832-2662-4ab4-be02-cfbeb933f44b.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/SIGL6YW7MNGQJAXYOOM36JKVK4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BNHBFLSEHBBGBEEQAWGAG6FHLQ.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1dc0e832-2662-4ab4-be02-cfbeb933f44b.jpg)