Why the End of Quantitative Tightening Matters

Fed officials have been debating how to wind down the policy.

On Wednesday afternoon, the Federal Reserve announced an important change in its strategy for reducing the bonds it holds on its balance sheet—a process known as quantitative tightening. Here’s a look at what that means for the markets and investors.

While most investors are focused on when the Federal Reserve will be cutting interest rates, there’s another key policy lever officials have been considering: its steps to reduce the amount of bonds it holds.

Quantitative tightening has been in place to unwind the massive number of bond holdings the Fed bought to pump money into the economy during the pandemic-driven recession (quantitative easing). Officials have been contemplating the end of quantitative tightening. Here we’ll delve into the history of quantitative easing and tightening, then discuss the mechanics of tightening and its associated risks.

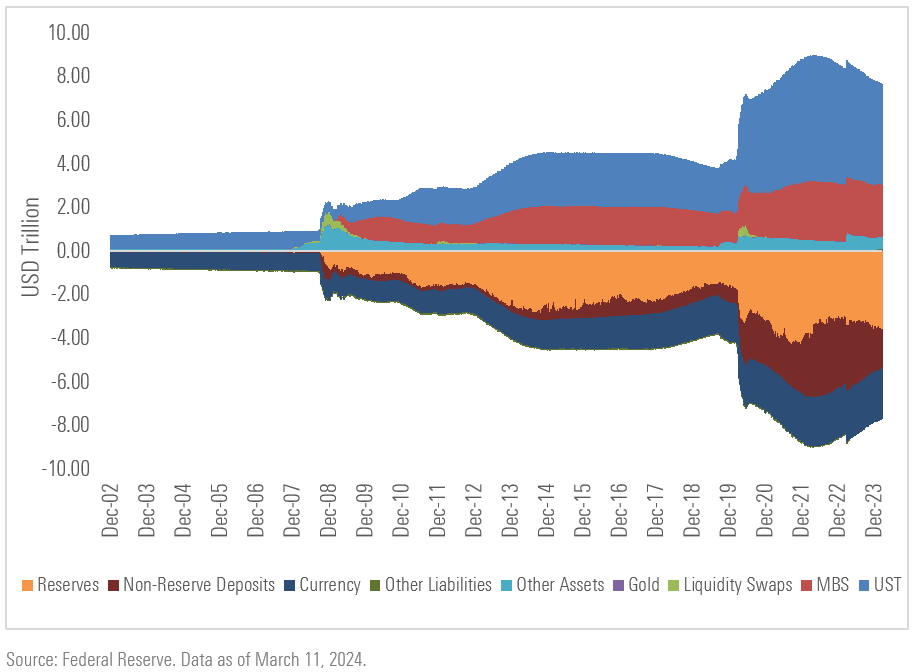

Federal Reserve Balance Sheet - Assets and Liabilities

What Is the Fed’s QE?

Open market operations—the purchase or sale of securities in the open market by a central bank—have a long history in the United States. Before the global financial crisis, the Fed regularly bought and sold Treasuries to maintain its targeted federal-funds rate, or FFR. This was possible because banks weren’t paid interest on the reserves they held at the Fed, so they limited their allocation to the level mandated to meet the banking needs of their customers. Small shifts in the supply of reserves, influenced by the Fed’s open market operations, could move the FFR one way or another, keeping it at the target for monetary policy purposes.

The global financial crisis changed this and a whole lot more. The Fed shifted from a single FFR target to a range. In December 2008, it set a 0%-0.25% target range to stimulate economic activity. The economy remained frozen, so the Fed did more: quantitative easing.

Between 2008 and 2014, it became a massive buyer of Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed debt, arguing that the purchases were necessary to maintain easy financial conditions, support economic growth, and, most critically, encourage job creation. It took a page from the Bank of Japan’s book, which began a quantitative easing program in 2001.

The Fed’s purchases over this period increased not only its security holdings on the asset side of its balance sheet but also the level of reserves in the banking system on the liability side. Reserves ballooned from $33 billion at the end of 2007 to $2.4 trillion in late 2014.

Growth in Bank Reserves, December 2007 vs. December 2014

After the crisis, the Fed entered a regime of ample reserves, and more recently abundant reserves. Under this paradigm, the central bank’s marginal buys and sells no longer influence the FFR. It thus uses another tool introduced during the crisis: the interest on reserve balances. The Fed began offering interest on bank reserves and used that interest rate to affect the FFR. The Fed later introduced the overnight reverse repurchase agreement, and it now relies on both administrative rates to steer the FFR into the FOMC’s target range.

The Fed’s Exit Strategy

Actually, there isn’t one, on the whole. The Fed has not indicated whether it intends to return to limited reserves. And moving $7 trillion off its balance sheet would be no easy feat. The central bank doubled (or maybe quadruped) down on quantitative easing at the height of the covid-19 pandemic, moving aggressively into the bond market by making an open-ended promise to purchase $500 billion of Treasuries and $200 billion of mortgage-backed bonds. With credit markets also in turmoil, the Fed announced issuance support and an investment-grade corporate bond-buying program. These announcements alone calmed the market; ultimately, the Fed only bought $14 billion in investment-grade credit.

But engaging in multiple rounds of quantitative easing and remaining committed to higher reserves for the foreseeable future doesn’t mean the Fed wants to maintain its balance sheet at these bloated levels. Part of the rationale is, of course, monetary policy. Quantitative tightening pairs nicely with raising rates, though since there is no limit to how high the central bank can raise rates, tightening isn’t necessary for restrictive policy. There are other, more strategic reasons.

The long-term assets on the Fed’s balance sheet expose it to interest rate risk, so shrinking its assets reduces the potential for loss. Additionally, intervention in the mortgage market means the Fed has allocated capital to an area of the economy that most would argue is beyond the scope of its mandate. Getting rid of those bonds helps restore the central bank’s evenhanded reputation. Finally, reducing its balance sheet in good times gives the Fed firepower to add back in future crises.

What Is QT?

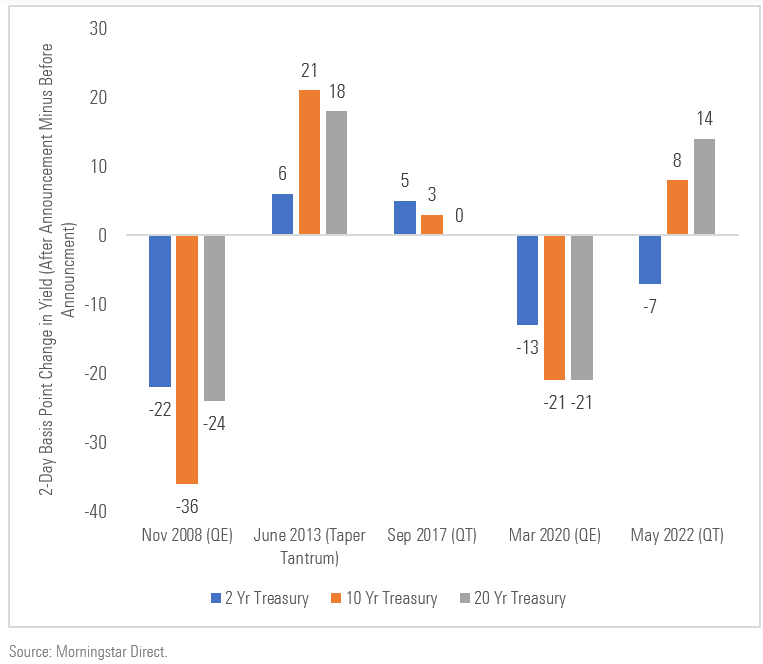

So how does quantitative tightening work best? Well, not with a big bang. While surprise announcements of quantitative easing have calmed investors during past crises, the reverse can cause panic even in good times. The Fed learned the downside of surprise pullbacks with the 2013 “taper tantrum”, wherein yields spiked in response to Chair Ben Bernanke’s suggestion that the central bank was considering an end to quantitative easing. Hence the “watching paint dry” approach that Philadelphia Fed President Patrick Harker described in 2017. That year, the Fed softly announced tapering plans on April 5, June 14, July 26, and Sept. 20, before finally beginning the program in October. In 2022, the Fed’s announcements were similarly well-telegraphed.

Market Reactions to Quantitative Easing and Tightening Announcements

Rather than actively selling bonds to the market (the symmetrical action to active buying in quantitative easing), the Fed takes a more passive posture when tightening, allowing a predetermined amount of bonds to roll off its balance sheet as they mature. This approach is consistent with the quiet approach the Fed relies upon to avoid disrupting the financial plumbing. Ultimately, the aim is that quantitative tightening operates quietly in the background while the market focuses on Fed statements and the FFR to interpret policy.

Much Ado About Nothing?

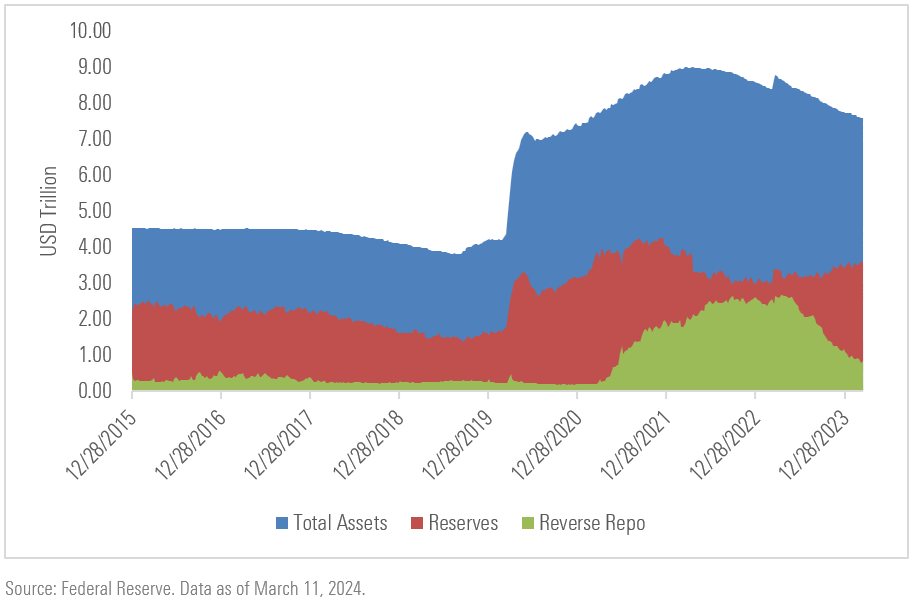

So they’ve thought of everything? No concerns here? Not quite. When Fed Chair Jerome Powell announced quantitative tightening in June 2022, he reminded investors “how uncertain the effect is of shrinking the balance sheet.” He discovered this uncertainty the hard way. Shrinking the asset side of the Fed’s balance sheet means fewer reserves for US banks and other non-bank financial institutions on the liability side.

Federal Reserve: Total Assets, Bank Reserves, and Reverse Repo Reserves

A 2018 policy paper by Falk Brauning with the Federal Reserve of Boston found that the liquidity effect of quantitative tightening depended on the number of reserves in circulation. So as quantitative tightening continues, each additional dollar lost will have a greater impact. We saw this play out in 2019. As the Fed’s quantitative tightening program continued, reserves drained, eventually spiking overnight lending rates.

The 2019 Scare

Likely for this reason, the Fed has stepped up scrutiny of its quantitative tightening program before announcing a tapering plan. The central bank has said it aims to move reserves from today’s “abundant” levels to “ample” levels to ensure the same scare doesn’t recur. The Fed’s definition of “ample” is as squishy as it sounds: a reserve large enough that the FFR changes slightly when the quantity of reserves in the banking system changes. The Fed further signaled a coming shift at its March 2024 meeting, with Powell saying at the press conference that it would be “appropriate to slow the pace of the runoff fairly soon.”

Caution is probably doubly warranted, given the slow-moving commercial real estate crisis. As banks risk hits from defaulting loans, the Fed will likely want to ensure no additional strain from inadequate reserves or spiking overnight rates.

Yet as one might guess from the nontechnical, imprecise definitions of “abundant” and “ample,” there is no consensus about when reserves will fall below questionable thresholds. The best the Fed can do is closely monitor reserve levels relative to need and historical benchmarks, evaluate the runoff pace, and observe overnight rates. In August 2023, St. Louis Fed economists Amalia Estenssoro and Kevin Kliesen calculated “ample” reserves as consistent with 10%-12% of nominal GDP, which at the time was about $2.7 trillion-$3.4 trillion.

Still, it’s a real-time calculus, and a shrinking balance sheet doesn’t equal shrinking bank reserves. This means when the Fed begins to slow, the runoff remains in question, as does the actual end to tightening.

Morningstar Investment Management LLC is a Registered Investment Advisor and subsidiary of Morningstar, Inc. The Morningstar name and logo are registered marks of Morningstar, Inc. Opinions expressed are as of the date indicated; such opinions are subject to change without notice. Morningstar Investment Management and its affiliates shall not be responsible for any trading decisions, damages, or other losses resulting from, or related to, the information, data, analyses or opinions or their use. This commentary is for informational purposes only. The information data, analyses, and opinions presented herein do not constitute investment advice, are provided solely for informational purposes and therefore are not an offer to buy or sell a security. Before making any investment decision, please consider consulting a financial or tax professional regarding your unique situation.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1bb3b7d2-89c3-40c6-ad6d-01d4f0004f7a.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/4QBQ2NBJMFG5HGQTDEYCXY5OOI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/2RGHQJTF4ZEURNSAGBY7CSHCUQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EAAEIIRVVNE7HNVXBSGTD3WPSI.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1bb3b7d2-89c3-40c6-ad6d-01d4f0004f7a.jpg)